‘Alas ng Bayan’ – a fraction of contribution By...

Read MoreAlas Ng Bayan 1.0

Aesthetic Concept: Alas and Five Aces

Alas ng Bayan is about five remarkable Filipinas who resisted national oppression, social injustice, and false gender normatives at different junctures of Philippine history.

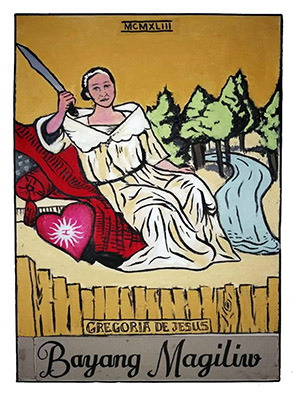

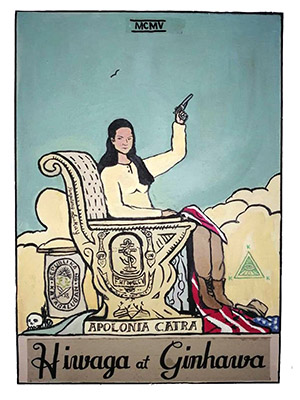

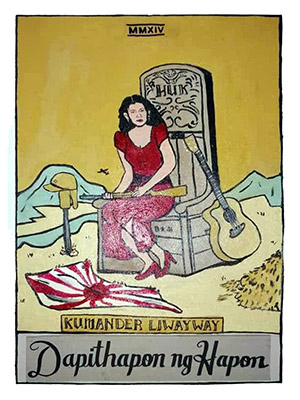

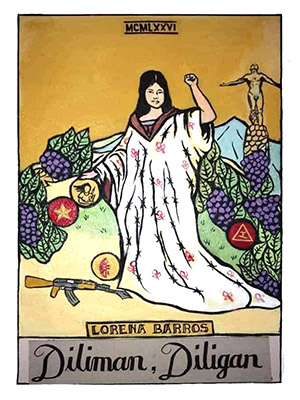

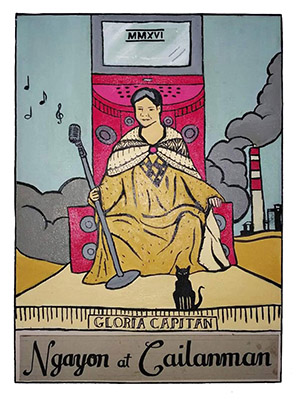

As the artworks deal with historical truths and the surreal, the Alas ng Bayan paintings were rendered in the style of Tarot cards or sakla, the card game used often in urban areas, many times in working class neighborhoods and during funeral wakes. Early in its history, the Tarot was used as playing cards by noble families in Italy. It was in the nineteenth-century that the Tarot card was linked to witchcraft and religion. Spiritual and esoteric groups have since considered the Tarot a body of knowledge compromising different archetypal images that cross linguistic, cultural, geographical, and temporal barriers.

Like the Tarot, the Alas ng Bayan paintings mirror similar mysticism while provoking its viewers to engage, if not decode, subtle symbolisms placed throughout the images. Alas is a local word for ace, a card that in most games is ranked as the highest, e.g. the ace of diamonds. It connotes a winning card or a secret advantage, for instance, “an ace up one’s sleeve.” As an adjective, its synonyms are excellent, outstanding, masterly, virtuoso, and first-rate. As a noun, an ace is equivalent to a champion, a doyen, an expert, and a master.

Can a normal card game have five aces? There are only four suits in typical poker games: diamonds, hearts, clubs, and spades. Aces with all four suits in one hand are called cuadro de alas (a winning hand bested only by the rare Royal Flush). Yet the Alas ng Bayan paintings convey a fifth suit, suggesting women and heroism as notions that refuse to be contained by conventional definitions. A quinta de alas suit seems absurd even as a linguistic Creole contrivance. But the framing seems apt; we live in interesting times when more and more young people, especially young women weary of corrosive machismo, refuse to play by the rules, openly choosing to resist and defeat toxic masculinity.

In Latin numerals as well, quinta is the female equivalent of quintus, which translates to “fifth”. Quinta is an anomaly. It’s etymology is linked to quinta essentia which translates as the fifth element and is where the word quintessential comes from. Some discussions link quinta to pre-atomic theory where four “known” elements or essences are identified — Earth, Air, Fire and Water — in addition to a putative fifth element, quinta essentia. The fifth element was believed to be superior to the other elements, and so, “quintessential” has come to mean something that is superior. The fifth element was believed to be more subtle, permeating the fabric of things and was thought to be more difficult to find or to isolate. This is why the word quintessential is used often today to describe the essence of things nearing perfection. In this light, Oriang, Apolonia, Liwayway, Lorena, and Gloria are without any doubt quintessential to Philippine history.

Paintings

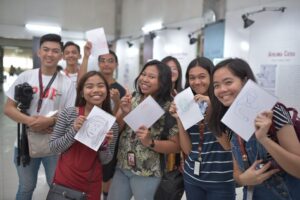

The works of art cover five Filipinas each of whom lived in different historical periods. They have been chosen as subjects as they are a good mix of women across generations, across key periods in our history, across different acts of resistance, and across a range of popularity, meaning, from the well-known to the unknown.

Painting Notes

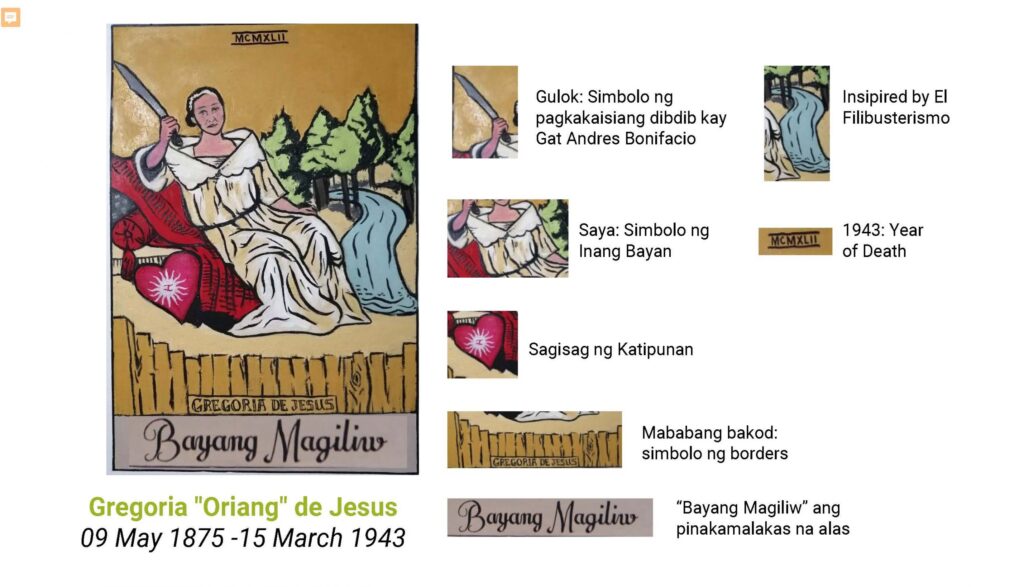

What explains the words in this painting? Did you know that Oriang’s second husband, Julio Nakpil, a national hero, musical composer and one of the most respected leaders of the Katipunan, used “Giliw” as his alias? Oriang’s words are a constant reminder to all about a basic cosmic truth that many often forget: “Fear history, for it respects no secrets.” Behind Oriang is a forest, through which a river flows and which paradoxically appears to come to a full stop. Perhaps it is the artist’s statement concerning the continuities and discontinuities of history and memory? Oriang appears relaxed in the painting while leaning on a red pillow draped with crimson fabric. Yet she holds aloft a saber. Why did the artist place a heart-shaped symbol beneath the hero, and what is the script at its center? What does it mean? Why did the artist paint in the foreground a fence, which provides little obstruction? In her autobiography, Oriang recalls her disposition while helping throw off the colonizer’s yoke: she always took sides. She was no fencesitter, for sure.

Symbols and References

Painting Notes

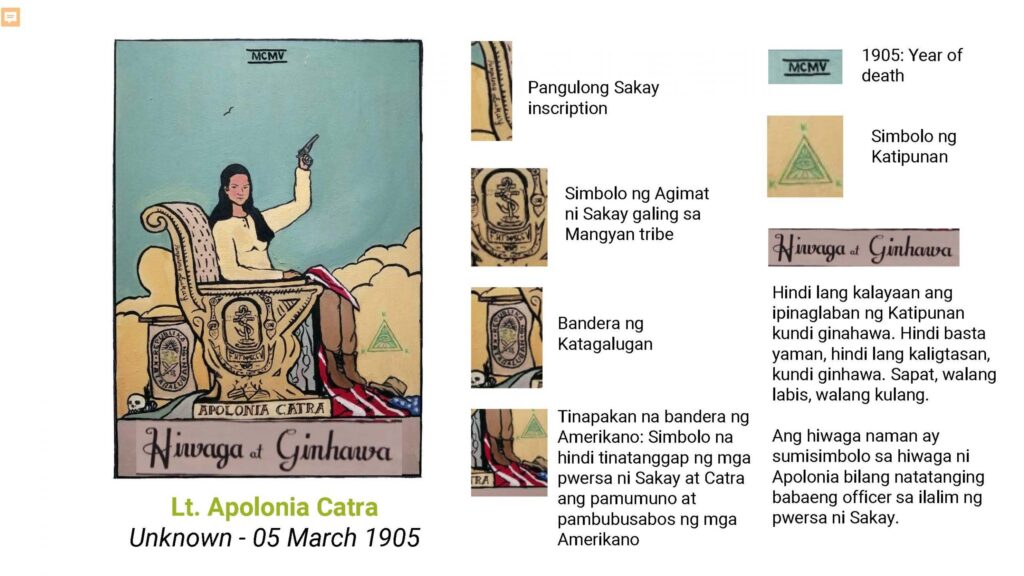

What might be behind the title of the painting? Can you recognize the symbols on Apolonia Catra’s chair? What does it mean? Is it an amulet? Who might have worn it? Why is there a name on the back rest? Whose name is it? What might explain the lone bird painted in the horizon? What is the real story behind the seemingly ‘regionalistic’ emblem behind Apolonia? Questions abound.

No photos exist to indicate what Apolonia Catra might have looked like. Why did the artist use a young Nora Aunor as his model? Do you agree with his choice? Who else should he have considered as his peg? If you had painted Apolonia, what elements would you have integrated based on George Yarrington Coats description of her in his unpublished thesis on the Philippine Constabulary? Why do think there is so little material about women heroes in our country’s history? Gregoria de Jesus once said: “Remember always the sacred teachings of our heroes who sacrificed their lives for love of country.” How would you choose to remember Apolonia Catra?

Symbols and References

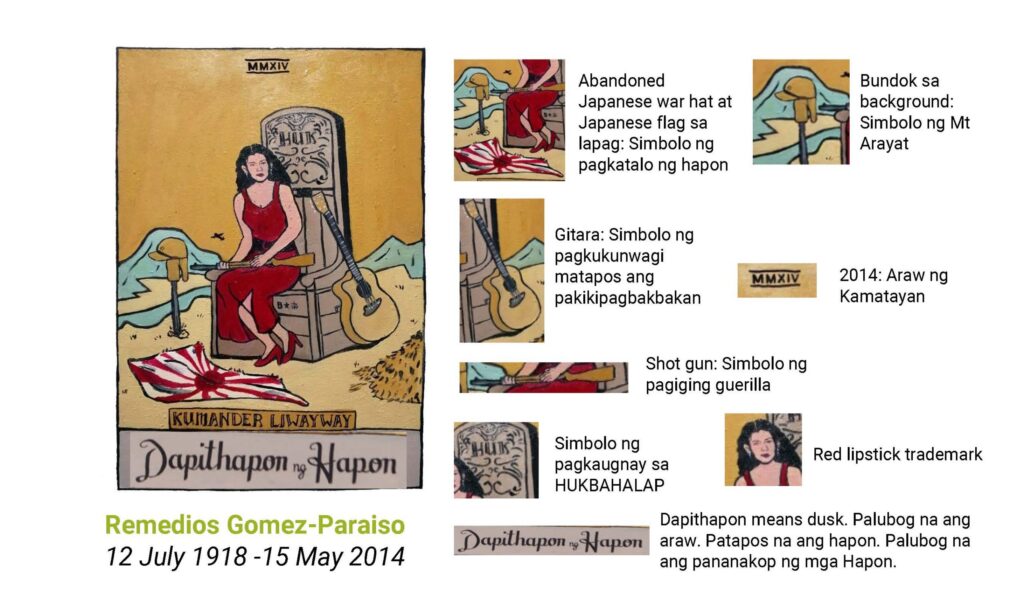

Painting Notes

What is the strange headgear on top of the stick by the side of the hero? What does it symbolize? What explains the lone bird in the horizon? What explains the presence of a guitar in the painting? The carving at the back of Kumander Liwayway is the artist’s way of showing the craftsmanship of Pampanga. Even though, at great cost, they helped repulse the imperial forces of Japan, Remedios Gomez-Paraiso and her comrades were hunted down and forced again to fight from the mountains soon after Japan’s surrender. Why? What new cause did Kumander Liwayway come to champion, and how did the term “Huk” evolve? The fierce courage of Kumander Liwayway during wartime was well known. She was feared by Japanese soldiers and the Philippine armed forces. Yet few know the extent to which she was also intensely embraced by her loved ones, judging by the way her children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren, received her motherly affection and the incredible caring she showered on her family.

Symbols and References

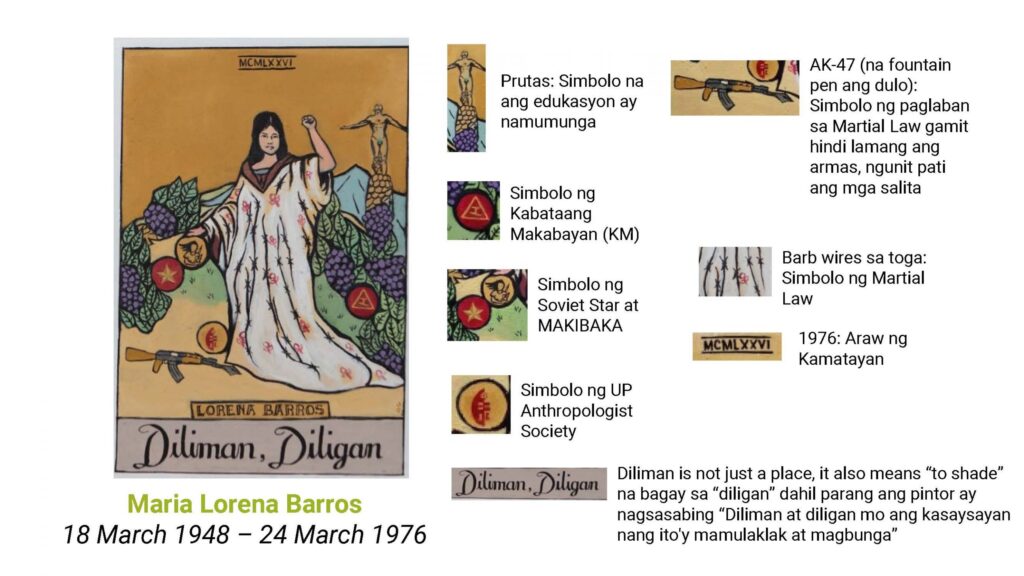

Painting Notes

What explains the title of this painting? Can you identify the four circular logos surrounding Lorena? Why do you think the artist chose white as the color of the hero’s toga, and what might the symbols in the fabric mean? What do fruits, or grapes, in Tarot symbolism represent? What does the mountain behind the Oblation stand for? Questions abound. Find out more about the rich, haunting, inspiring and textured life of Lorena Barros from the book by Pauline Mari Hernando, Lorena: Isang Tulambuhay, published by the University of the Philippines Press.

Symbols and References

Painting Notes

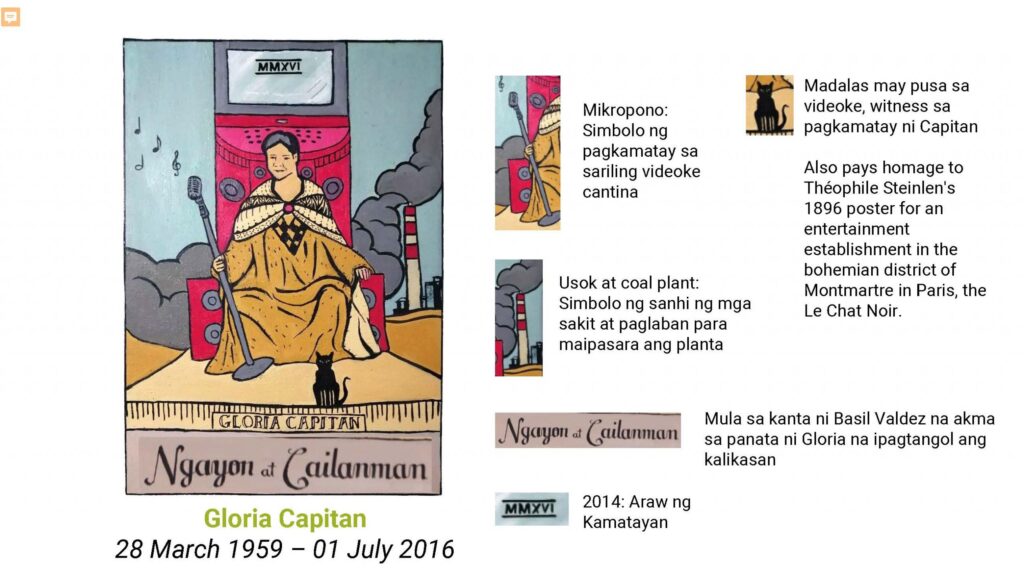

Do you recognise the machine behind Gloria Capitan? What is the facility billowing filthy smoke behind the hero? The black cat in the foreground seems to pay homage to Théophile Steinlen’s 1896 poster for an entertainment establishment in the bohemian district of Montmartre in Paris, the Le Chat Noir. What explains the title of the painting, and why is it spelled differently?

Symbols and References

What's New?

Alas ng Bayan: Intersections of history, feminism, and the climate crisis

Alas ng Bayan: Intersections of history, feminism, and the climate...

Read MoreAlas ng Bayan: Women, Memory, and History

Select Alas ng Bayan: Women, Memory, and History Alas ng...

Read MoreCheck Out These Art Exhibits Featuring Some of the Greatest Filipino Heroines

Check Out These Art Exhibits Featuring Some of the Greatest...

Read More